Two years ago at the time of my 50th birthday, I created a blog with the full title of The Word Guy: Adventures in Etymology. At the time, I was unsure how long I could keep it going and what it would lead to – if anything.

Two years on, the blog is still running and I have added the Tweetionary, which is based on my daily tweets of word etymologies.

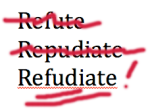

So it’s time for a regroup and, more significantly, a re-branding. Those of you in the business world will recognize that such a move is usually a result of one of two event; either because your product sucked and needs a make-over or (b) someone has slapped a trademark suit on you for infringing on their mark.

Surprisingly, in this case, it’s neither.

I have known for some time that I am not the only “Word Guy” on the block, and that there is another one in West Hartford, Connecticut, who is a teacher and writer, and has a column in words and language. His name is Rob Kyff and we have never corresponded, although I’m pretty sure he knows about this Word Guy if only because when you do a Google search for “The Word Guy,” I come out on top.

Now, Rob has been “The Word Guy” for longer than I but my using the name has never bothered him and he doesn’t appear to have registered “The Word Guy” as a trademark. Nevertheless, I do feel a twinge of guilt about using “The Word Guy” as a mark when he had it first.

So as I am planning the next few years of activity, one of the things on my list is to register a trademark to allow for some expansion of what I do and to protect against potential issues in the future. Much as I would like to hold “The Word Guy,” it wouldn’t stand up because Rob clearly has the common law mark simply through having used the phrase earlier than I did. Although I started using “The Word Guy” without knowing about Rob, now that I am looking toward branding, I don’t want to cause any trouble by using it. On that basis, I am happy to cede the “Word Guy” to Rob and move forward with some other trademark.

Enter the Etyman™.

The word is a coinage and so better as a brand name because it isn’t a common word. Clearly it plays on the word etymon, and if I’d been Scottish, I would have been tempted to go with “The Ety Mon” as mon is Scottish dialect for man. However, “The Ety Man” seems fine to me, and the simpler Etyman works. It also makes for a much shorter Twitter(TM) name of @etyman – and in the world of tweeting, characters matter!

The Grand Design

1. Seeing as there is no pending lawsuit, there’s no need for a “cease and desist” at the current Word Guy site so the transition will take a few months. All new post will appear here at The Etyman™ Language Blog and the old ones will stay at thewordguy.wordpress.com indefinitely.

2. My Twitter feed will change from twitter.com/thewordguy to twitter.com/etyman, a process that will take some time as it means people will have to actively switch. For about three months I will run them in parallel but the aim will be to phase out @thewordguy as soon as possible.

3. The logo will probably change. My current little owl is cute and royalty free but I’d like to create a more personalized identity with an new graphic. Again, there is no time scale other than “soon.”

4. The content of The Etyman Language Blog will start to include posts of a more generic linguistic, some of which may be much shorter than the current weekly post and more “observation” and “opinion” than the simple definitions and examples I currently provide.

So that’s about it for 2010. Bear with me through the changes and add this new site to your favorites. Join me over at;